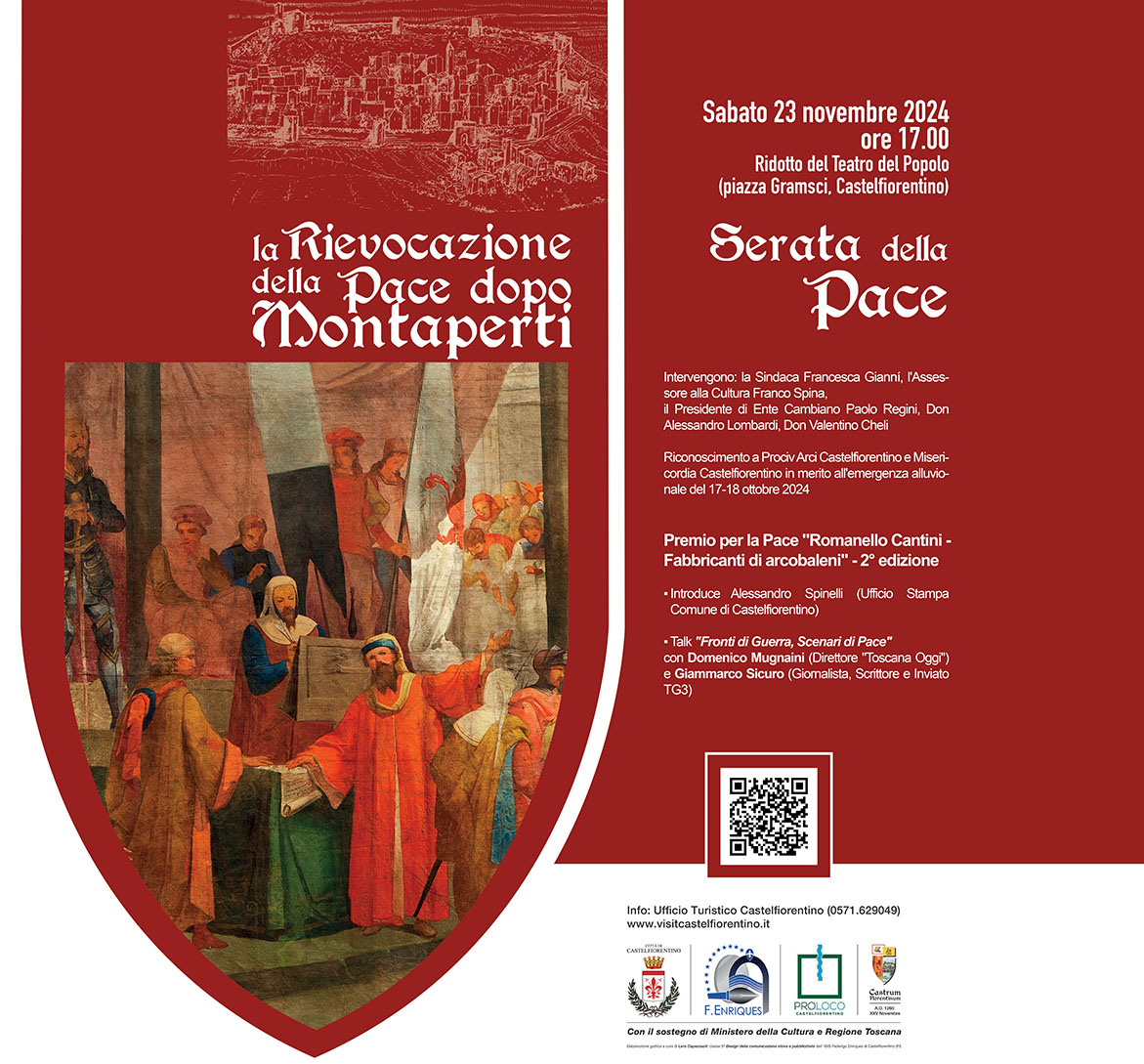

Peace after Montaperti: in Castelfiorentino the historical re-enactment

of the “signing” between Guelphs and Ghibellines after the “great massacre” narrated by Dante Alighieri

From Saturday 16 to Sunday 24 November, medieval festivities in the streets and squares of the centre, with two weekends full of proposals and shows.

Combat tournament, medieval market exhibition, arts and crafts market, medieval encampment and dances, games and falconry, parade and historical procession.

It was one of the bloodiest battles of the Middle Ages, also recounted by Dante in the “Divine Comedy”, who dwelt on the “great havoc that the red-coloured Arbia wrought”. An epic clash, which at Montaperti saw Guelph Florence and Ghibelline Siena involved, and which ended with a Peace signed precisely in Castelfiorentino on 25 November 1260.

And it is precisely on the value of this recurrence, namely Peace, which with the power of its universal message is addressed to all peoples to reconcile conflicts of any nature, that the ‘Historical Re-enactment of Peace after Montaperti’ takes place in Castelfiorentino.

The historical centre of this village in the Florentine Valdelsa is immersed in the medieval atmosphere of the period, through a sequence of unmissable events.

For detailed information on the programme: Castelfiorentino Tourist Office (+39 0571.629049) or ufficioturistico@comune.castelfiorentino.fi.it.

HISTORY

Around the middle of the 13th century Tuscany was divided into independent states, distinct into Communes (made up of towns and castles) and Seignories, headed by noble families who had their own domains. The frictions and divergences that could even lead to conflicts were generated on two levels, which often intersected: the territorial level, fuelled perhaps by border issues, spheres of influence, commercial rivalries; and the political level, based on the clash and alliance between the three parties: Guelphs, Ghibellines, and Peoples. The former, as is known, were linked to the Papacy. The latter to the Empire, in the persons of the Swabian sovereigns. The commoners represented local interests and had no authority of reference. The factor that aggravated the crises between states was the ability of the Guelphs and Ghibellines to create supra-local alliances, dividing the ruling classes within themselves. After the death of Emperor Frederick II of Swabia in 1250, a populist regime had imposed itself in Florence, which thanks to a policy of equidistance between the two parties in play had gradually managed to extend its influence. The Ghibellines, however, reacted to this situation: and on two occasions (1251 and 1258) they organised revolts, eventually taking refuge – in 1258 – in Siena in exile. Pressure from the Florentine Ghibelline refugees, and promises of military aid from the last Swabian ruler (Manfred, King of Sicily, natural son of Emperor Frederick II) persuaded Siena to violate the 1255 trade agreement (the “society”), challenging Florence. The latter reacted by organising a military campaign in the summer of 1260, resulting in the disaster of Montaperti, where the Florentine army was heavily defeated by the Sienese. The “slaughter” of the Florentines was such that it was remembered by Dante Alighieri in the “Divine Comedy” (Inferno, Canto X) as “the torment and great havoc that the Arbia coloured red”. On a political level, the military defeat inevitably led to the fall of the populist regime of Florence and its allied regimes (with the sole exception of Lucca), reducing its role in Tuscany.

The Peace after Montaperti (Castelfiorentino, 25 November 1260)

The political and territorial reorganisation of the region took place through the signing – on 25 November 1260 – of two agreements between the Communes of Florence and Siena. The signing took place in a locality near Castelfiorentino, at the time a Commune subject to Florence, a place of strong strategic value for the control of Valdelsa, over which Siena wanted to extend its influence.

According to the practice of the time, the Municipalities of Florence and Siena were represented by Mayors – in practice special procurators, according to today’s legal terminology – who were appointed ad hoc: Lotteringo del fu messer Ubertino di Pegolotto for Florence, and messer Iacopo di Pagliarese and Buonaguida del fu Gregorio di Boccaccio for Siena. Let us examine them separately:

1) With the first agreement, Florence ceded “rights”, both public and private, held in a series of communities (Montepulciano, Montalcino, Poggibonsi, Staggia, etc.) and lordships. These “rights” – iura in the text, from the Latin ius-iuris – were understood at the time to mean legal relations such as private property rights, sovereign rights such as the collection of taxes, and personal bonds of loyalty and subservience in this case impossible to define due to lack of details. In essence, this agreement sanctioned the passage of communities and lords from the control of Florence to that of Siena.

2) The second agreement, called the “society”, was akin to a peace treaty proper. Through it, the two former belligerents put an end to their disputes, settled the issue of prisoners of war, pledged to recognise each other’s jurisdiction, promised aid and assistance, and entered into a new free trade agreement.